The Engine of Market Forces: Supply and Demand

00:00 / 00:00

Exploring similarities between seemingly unrelated things

Let’s start by talking about something that most people take for granted.

Is it grocery stores, is it the census, is it GPS, is it goldfish, is it frogs… maybe mangoes ?????

No, it’s markets.

Who decides the prices of mangoes/equities/kidneys and oil?

Mangoes are great, but where do you think mangoes came from?

The plant, the farmer, the market, the grocery store, the miracle of life?

Look around you. Where did all that stuff come from? And who made it? And why?

Well, the answer is simple, but it’s underrated.

Markets.

The Power of Voluntary Exchange

So a market is any place where buyers and sellers meet to exchange goods and services. The key to markets is the concept of voluntary exchange. That is, that buyers and sellers willingly decide to make a transaction.

Let’s say you go to a farmer’s market and you buy a box of 500gms mangoes for Rs 30. You value the box of mangoes more than the Rs 30 you gave up to get it.

The seller valued the Rs 30 more than the box of mangoes. The transaction’s a win-win because you got your mango and the farmer got his money. You both felt better off; that’s voluntary exchange.

This same process happens in the labor market. Say that instead of the farmer’s market, you bought your mangoes at your local supermarket.

The cashier voluntarily decided to work there. He values the Rs 100 an hour he makes there more than he does sitting at home watching Netflix.

At the same time, the owner of the store values the labor of the cashier more than the Rs 100 an hour she pays him.

And so it goes, on and on, all the way up the chain of production, from the driver that delivered the mangoes to the farmer that grew it to the tractor that the farmer purchased.

The point is that markets are everywhere and most are based on voluntary exchange.

The part of all this that most people take for granted is how efficient the system is. Competitive markets turn out to be pretty great about allocating or distributing our scarce resources towards their most efficient use.

So if farmers produce, like, too many mangoes, then the price will fall as sellers try to sell them off.

Lower prices means less profit for the mango farmers, and those farmers will have an incentive to produce something else like onions or corn.

So if farmers don’t produce enough mangoes, buyers will bid up the price and the farmers will have an incentive to produce more, which then drives down the price.

That’s like magic, except it’s not.

Myths About Businesses and the Market’s Role in Price Determination

The information that markets generate to guide a distribution of resources is what economists call a signal.

If mangoes are brown and nasty then no one’s gonna want to buy them, and if the tractor’s a piece of junk, the farmer’s gonna tell other farmers to buy some other tractor.

Now, ideally the eventual result of voluntary exchange is that sellers can’t make themselves better off without making something that makes buyers better off.

Businesses, and in particular large corporations, are often villainized as greedy, heartless institutions that take advantage of consumers.

But if markets are transparent and buyers are free to choose, then businesses will have a hard time taking advantage of people.

Now obviously greed and deception happen in real life, and there are situations where consumers don’t have a choice.

But for the most part, if you really don’t like the policies or practices of a particular company, then don’t shop there.

After all, in the free market, every rupee that is spent signals to producers what should be produced and how it should be produced.

Something simliar to a startup that relies on signal from their customer through feedbacks.

We’ve established that prices and profit (signal) determine where resources should go, but where do prices come from? Who determines the price of my box of mangoes?

To answer that, we’re gonna draw – get ready for it – supply and demand. Let’s see some geeky graphs.

If there’s only one thing you should learn in Economics, it’s supply and demand. Let’s use the market for mangoes to help us understand this concept.

What is Supply and Demand in Economics?

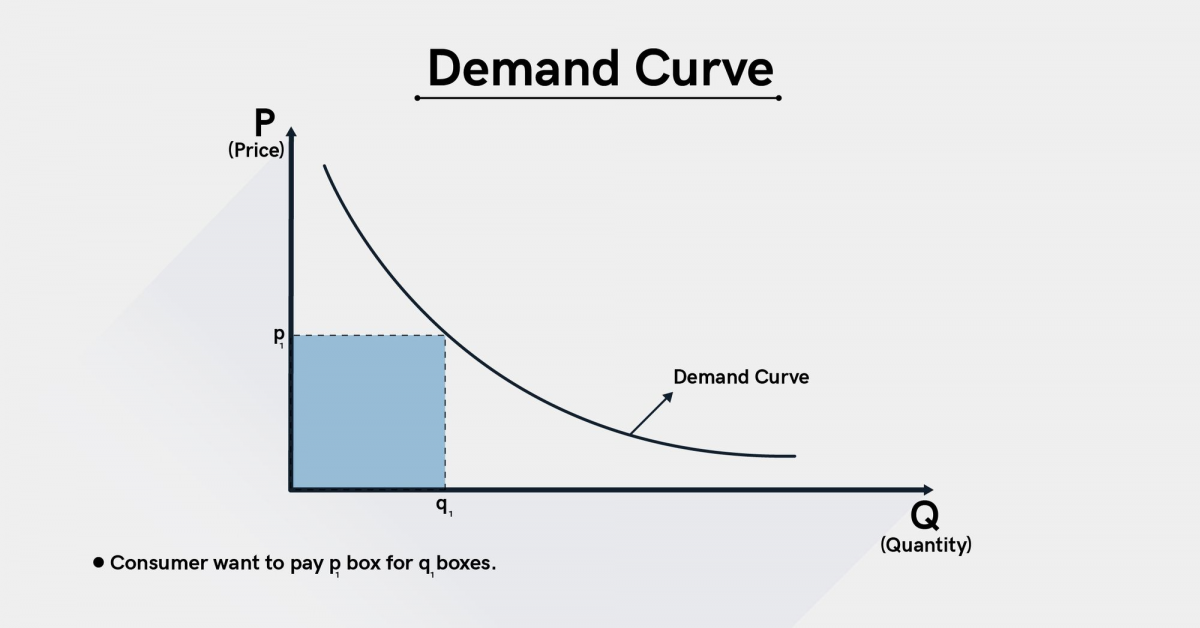

Up here on the Y axis, we have the price of mangoes, down here on the X axis we have the quantity of boxes.

Let’s start by looking at buyers and how they respond to a change in price. If the price per box goes up, then some buyers will go buy other vegetables or they’ll go on that all fruit diet.

The point is, they’re gonna buy less mangoes. And if the price goes down for mangoes, then people are gonna buy more.

This is called the law of demand: when the price goes up, people buy less, when the price goes down, people buy more.

On the graph it’s show by a downward sloping demand curve.

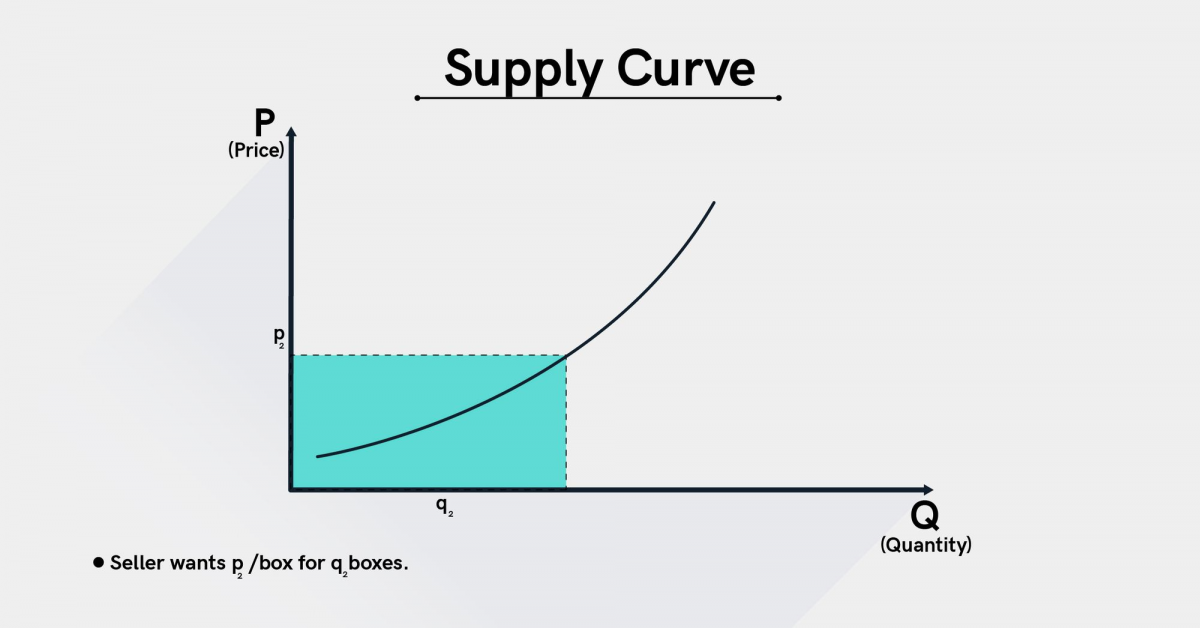

Now let’s think about sellers like the farmer in the farmer’s market. If the price of per box mango go up, then that farmer will make more profit, so will have an incentive to produce more.

If the price goes down then he’s not gonna want to produce. That’s called the law of supply, and on the graph it’s shown by an upward sloping supply curve.

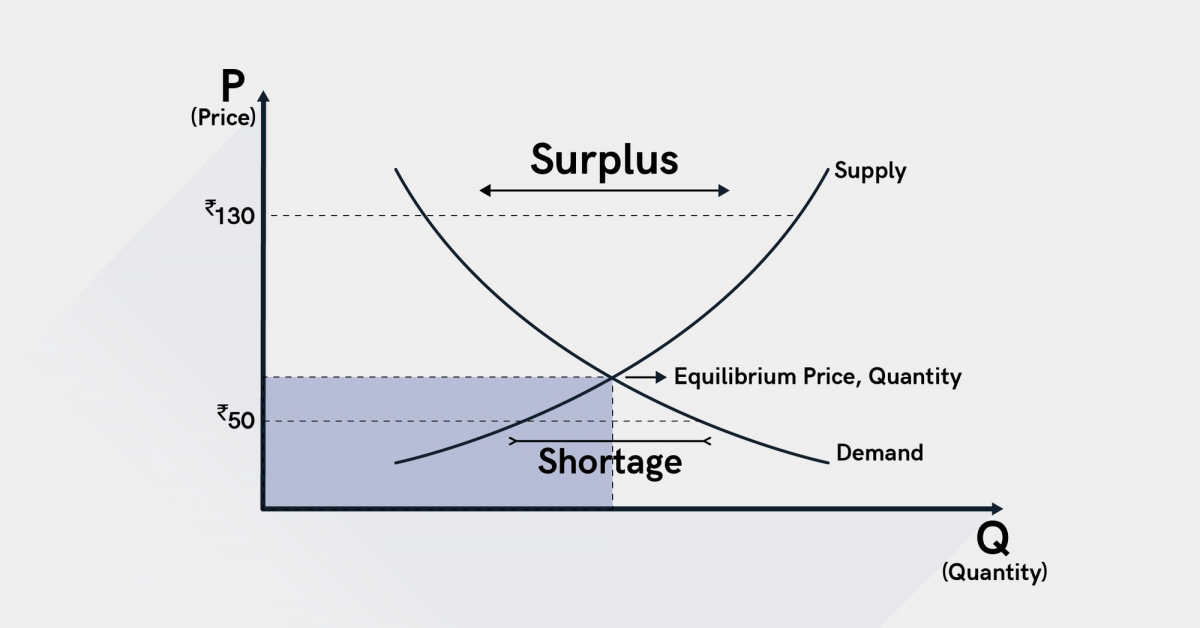

Now let’s put supply and demand together. If the price is really high at Rs130 then producers would like to produce a lot of mangoes, but consumers won’t want to buy them. This mismatch is called a surplus.

And if the price goes down for mangoes, let’s say down to Rs 5, then buyers want to buy a whole lot, but producers won’t have incentive and they’ll produce very little.

At the end you have mismatch, but this one’s called a shortage.

And there’s only one price where the quantity that buyers want to buy is exactly equal to the quantity that sellers want to sell, and it’s right here where supply equals demand.

The price is called the equilibrium price, and the quantity is called the equilibrium quantity.

Okay, sure your graph makes sense, but the price of mangoes isn’t always Rs 30 per box of 500gms ; sometimes it goes up to Rs 40, and at local, artisanly grown mangoes.

The fancy fancy mangoes, can cost upwards of Rs 80 for 500gms. I guess that is a topic for another time. We’ll stick to normal mangoes.

In fact, the prices for all sort of stuff change all the time. External forces can shift both the supply and demand curves, changing the equilibrium price and quantity.

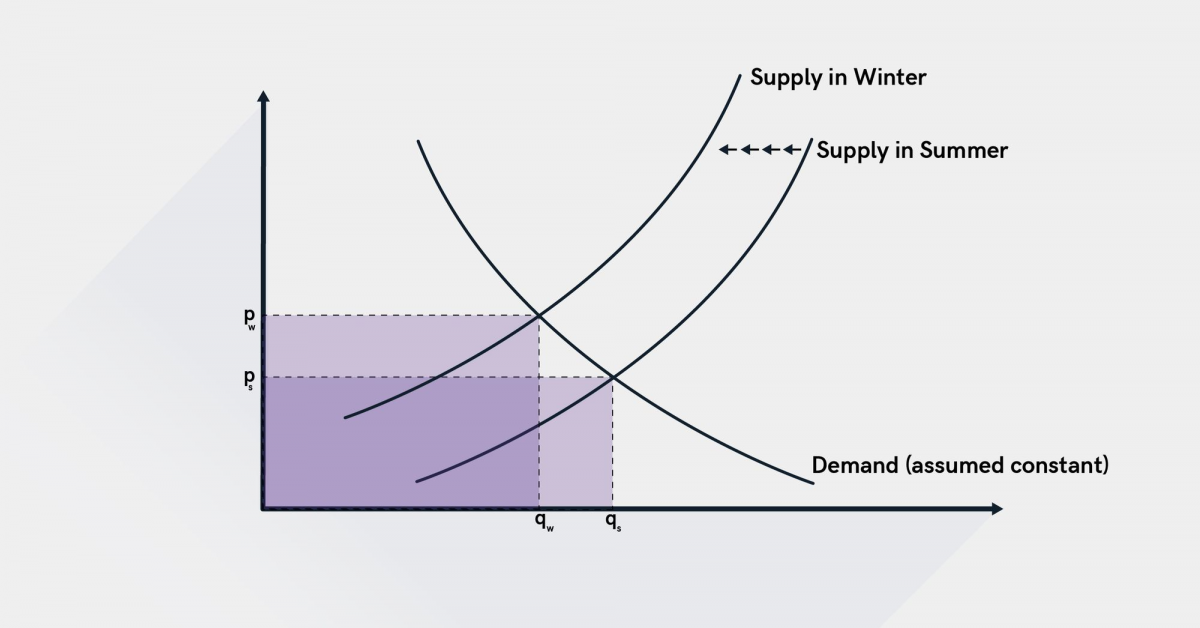

For example, let’s assume that this graph shows the demand and supply of mangoes in the summer. What happens in the winter? Will the change in weather affect buyers’ demand? Or producers supply?

Spoiler alert: it’s supply. Colder temperatures make it harder to grow mangoes. The result is the entire supply curve is gonna shift to the left.

This is because at all possible prices, there’d be fewer mangoes produced. That’s it.

This graph is just a tool that economists and everyone else used to show the results of a change in a market.

I know it seems complicated at first, but there are really only four things that can happen in a market. Supply can decrease, Supply can increase, Demand can decrease,

or

Demand can increase.

Some people might wanna talk about a price being fair or right. Well, that all depends on your point of view.

The buyer always considers a low price to be a very fair price, while the seller considers it unfair and vice versa.

The Magic of Competitive Pricing

Economists don’t really like to push opinions about prices. Voluntary exchange suggests that the price is there for a reason.

Let’s assume the demand for mangoes inexplicably falls, so the demand curve shifts to the left and the equilibrium price and quantity fall.

Farmers might go to the government for assistance, but most economists would argue there’s no reason to bail them out. The market’s spoken. Mango season is so over.

Furthermore, if the government helps the farmers by giving them a subsidy, it would be putting resources towards something that society doesn’t value.

That would be inefficient. Luckily, every reasonable person on Earth values mangoes ????, so they continue to get produced.

Now, the downside is, the supply and demand model only applies to analyzing mangoes. Nah, I’m just joking; it applies to all sorts of stuff.

Let’s look at a market for a commodity known for its volatility, both because of its fluctuating prices and because sometimes, it explodes: Crude Oil .

Now when you see crude oil prices are moving all over the board, that’s just demand and supply.

For example in April 2020, an oversupply of oil led to an unprecedented collapse in oil prices, forcing the contract futures price for West Texas Intermediate (WTI) from $18 a barrel to around -$37 a barrel.

Why? Well, it was demand and supply. Increased supply and decreased demand. And that’s it. Now you can tell all your friends you understand supply and demand. It’s a big day for you. It’s a big day.

Market Regulation

So markets and supply and demand are awesome. But sometimes, they’re not. Think about the market for human organs?

After all, there’s a huge shortage, and thousands of people die each year waiting for transplants. Should there be a competitive market for human kidneys?

A free marketeer would say sure, why not? If a donor wants Rs 5L more than he wants his other kidney, why stop him?

Well… Ethics. There are several problems that arise with an unregulated market for human kidneys. First is the moral question, is it fair for a poor person who can’t afford a kidney to die while a rich person lives?

Well, probably…no, not at all. Another problem results in the law of supply. When there’s an increase in the price of kidneys, there’s an incentive for people to steal and sell kidneys.

In fact, the World Health Organization has stated,

“Payment for organs is likely to take unfair advantage of the poorest and most vulnerable groups, undermines altruistic donations, and leads to profiteering and human trafficking.

I mean, all bad things. Now, that being said, some people do support some kind of payment for organ donors?

Well, it’s because you can solve some of these problems with a market approach, but the market must be regulated.

Often family and friends are willing to donate a kidney, but they’re not a match for the patient. Economists generally support creating kidney exchanges.

Where pairs of willing donors are matched with strangers who agree to donate to each others’ loved ones. In both cases, the supply of donated kidneys would increase, which would alleviate some of the shortage.

Let’s think about stock market. We see prices of a stock go up and down all the time so fast. Why does that happen? Same answer, Markets.

Markets drive the price of a stock. When people believe that a stock is being sold for a discount on intrinsic value of stock, they jump to buy it.

If more and more people want to buy the stock, demand curve shifts to the right, which drives the prices of the stock up. And stock markets have gradually become heavily regulated to protect investors.

Like I’ve said before, free markets are awesome, but they can’t solve all our problems Sometimes, they need to be regulated, and sometimes, they should be avoided.

So there you have what, for most people, is the start and for many, the end of Economics.

Supply and demand.

Thanks for reading. I’ll see you next time.

The content on this blog is for educational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice. While we strive for accuracy, some information may contain errors or delays in updates.

Mentions of stocks or investment products are solely for informational purposes and do not constitute recommendations. Investors should conduct their own research before making any decisions.

Investing in financial markets are subject to market risks, and past performance does not guarantee future results. It is advisable to consult a qualified financial professional, review official documents, and verify information independently before making investment decisions.

Open Rupeezy account now. It is free and 100% secure.

Start Stock InvestmentAll Category