Advantages of International Trade: A Comprehensive Guidance

00:00 / 00:00

I acknowledge that intricate subjects such as Economics often come laden with profoundly abstruse terminology that can prove rather inscrutable for individuals of ordinary disposition to comprehend. Complex?

The Power of Economics

Simply put, Economics as a subject doesn’t have to be that complicated. Remember, Economics is the study of scarcity and choices.

In this article, let us explore the concept of specialisation in Economics, why international trade is not a political prerogative alone but makes economic sense.

We have limited resources, so we need a way to analyse the best way to use them. We need Economics to make wise decisions in the future, but it also helps us understand the past.

Most empires, wars, and human endeavours can be explained using Economics. All you have to understand is who wanted what.

The Indian struggle for independence wasn’t solely about achieving self-rule, it also arose from the desire to break free from economic exploitation imposed by colonial powers. It was rooted in economics.

Economics can explain so much about the world, and that’s why I am writing about this, and that’s what makes it the greatest subjects of all time.

Take that Computer Science!

The Evolution of Progress

Let’s stick with this history theme and talk about the progress of humanity throughout the ages.

Using measurements like life expectancy, child mortality, and income per capita, we can show the majority of humans that ever lived had terrible lives.

Statistically speaking. It wasn’t until the industrial revolution that people saw significant and sustained increase in their standard of living.

Populations skyrocketed, but so did life expectancy and food supplies and hospitals and eventually toilets and refrigerators.

Adam Smith on Specialisation

It was at the beginning of the industrial revolution that Adam Smith, the first modern economist, wrote his book “An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations” or AIITNACOTWON.

He sure wasn’t great at naming books, but he was really good at explaining the source of prosperity.

What Adam Smith concluded was specialisation, or what he called the division of labor, that made countries wealthy.

When I think of specialisation, I think of Domino’s where different workers have specific tasks like preparing the ingredients, making the pizza, putting it in the oven, taking it out and putting it in the box and then delivering it to our home.

This division of labor makes each worker more productive since they can each focus on the thing they do best, and they don’t waste time switching between jobs.

But specialisation goes beyond the assembly line for pizza.

To produce the yummy cheese, there was a dairy farmer who specialised in raising cows; the oven was designed and manufactured by people who specialise in engineering ovens;

Adam Smith quoted, “In every improved society, the farmer is generally nothing but a farmer; the manufacturer, nothing but a manufacturer.

The labour… necessary to produce any one complete manufacture, is almost always divided among a great number of hands.”

Pizza & Productivity Puzzle

Imagine what it would be like to make a pizza completely on your own. From scratch. It would be crazy!

You would have to grow the wheat and tomatoes and raise the cow, you’d make the flour, the cheese, the oven and the pan.

Without specialisation, if you want something, you have to make it yourself. And for thousands of years of human history, specialisation was, well, pretty minimal.

Of course humans specialised prior to the industrial revolution, it’s one of the marks of civilisation, but the modern era has taken this to the extreme.

Think of how many people from how many different specialised fields it takes to make a computer, all of them working in harmony so I can write my super profound thoughts in this article :P.

So specialisation makes people more productive, but Adam Smith said that it’s trade that makes them better off.

Assume that you can produce either pizza or t-shirts.

If you are way better at making pizza, then you should specialise in making pizza and then trade with someone else like Sheersham (Me) who’s way better at making t-shirts.

With trade, both of us can end up with more pizza and shirts than if we tried to make them on our own.

Economic Model

To fully explain this idea of the benefits of trade, I need to show you an economic model, but before we go any further, know that economists geek out over models and graphs.

Don’t get all worked up about the numbers; they’re not that complicated. Models are just visuals to help us simplify and explain concepts. It’s time for the model!

Production Possibilities Frontier

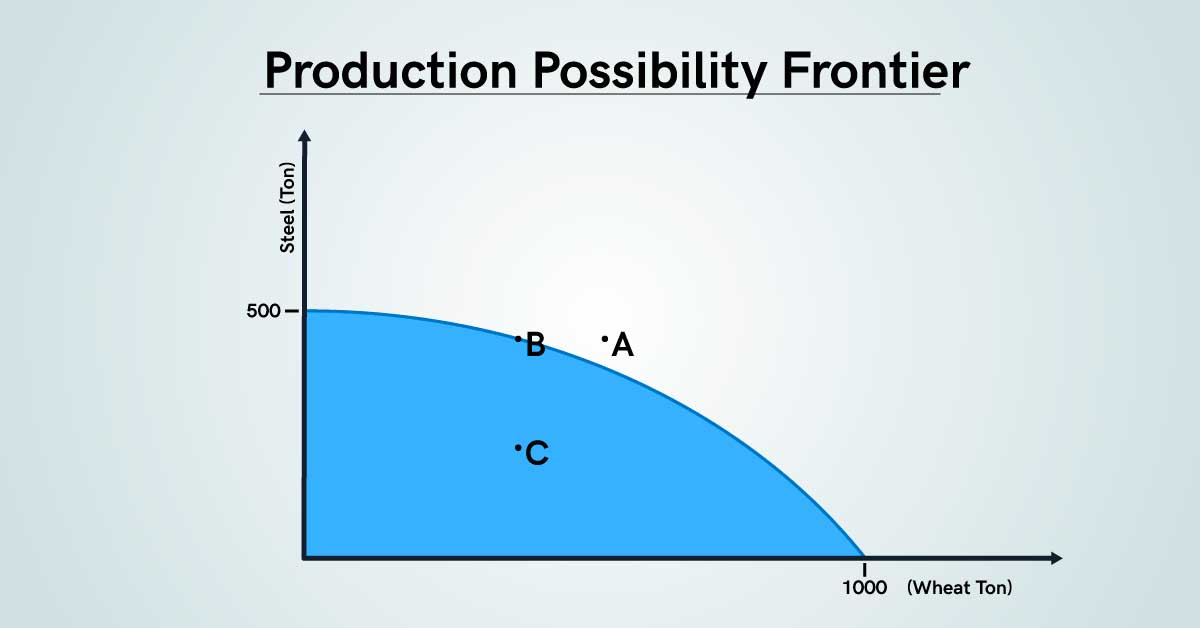

Now this is the first graph you’ll see in an Economics textbook. It’s called the production possibilities frontier, or PPF.

The PPF shows the different combinations of two goods being produced using all resources efficiently.

Now here’s a made up example. If India uses all of its workers and factories to produce Steel, it can produce 500 units per year, but they can’t produce any Wheat.

Now if they use all their resources to produce wheat, they can produce 1000 units per year, but they can’t produce any steel.

Now because India has limited resources, they can’t produce any combination beyond the production possibilities frontier( Point A ), so it’s impossible to produce 500 units steel and 1000 units of wheat.

Wait, I want to stop you here for a second. We don’t live in a world where there are only two things that a country can produce.

There are like a million things that India can choose to make: toilet paper, zippers, adorable stuffed kitty cats holding hearts, artisanal sauerkraut — we don’t live in a world of just wheat and steel, so what’s the real world value of the production possibilities frontier?

The idea is once you really understand that there’s trade-offs between producing two goods, that same logic applies for any number of goods.

Adding additional goods makes it more complex but doesn’t really add any more insights, so economists usually just stick with two goods.

Now, what if Indian companies mismanage their resources, employ steel factory skilled labour for farming and vice versa?

Well, they’d be at a point inside( Point C ) the production possibilities frontier, showing an inefficient use of resources.

So every possible combination inside the curve is inefficient, and on the curve( Point B ) is efficient and outside the curve is impossible.

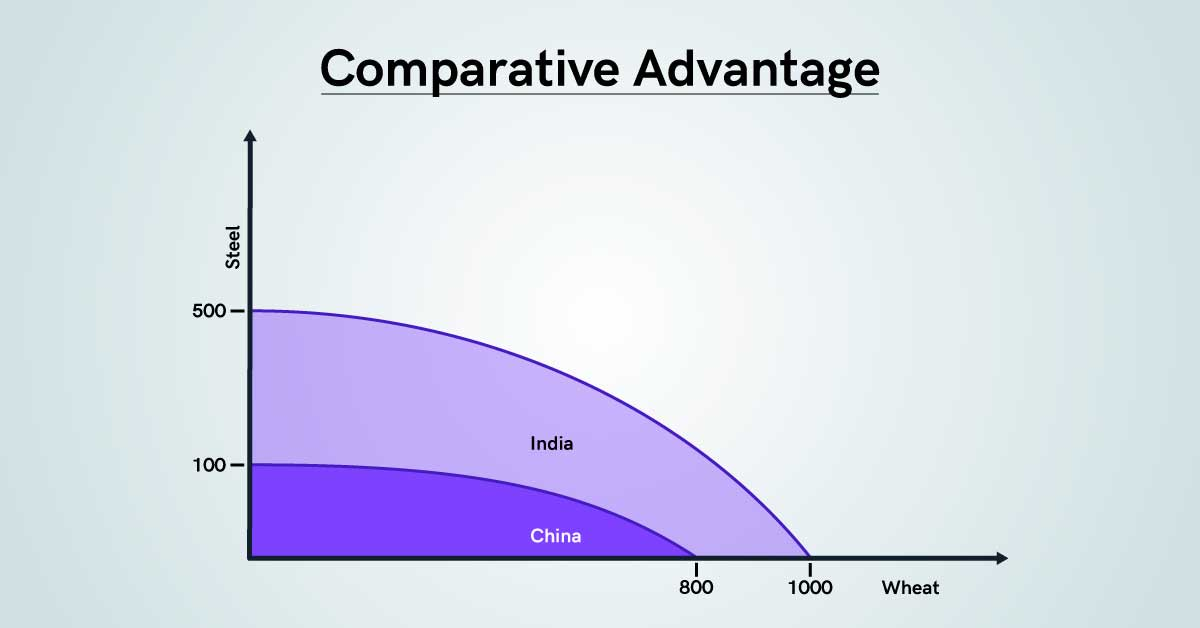

Now let’s compare this PPF to China’s. China can produce 100 units Steel per year or 800 units of wheat.

Absolute Advantage Theory of International Trade

Since India can produce more steel than China, they have an absolute advantage in the production of steel. India also has an absolute advantage in the production of wheat.

Since India can produce more of both goods, you might think there’s no reason to trade, that they should just produce both on their own.

Well, no. Remember, specialisation and trade makes people, and in this case countries, better off.

Comparative Advantage in International Trade

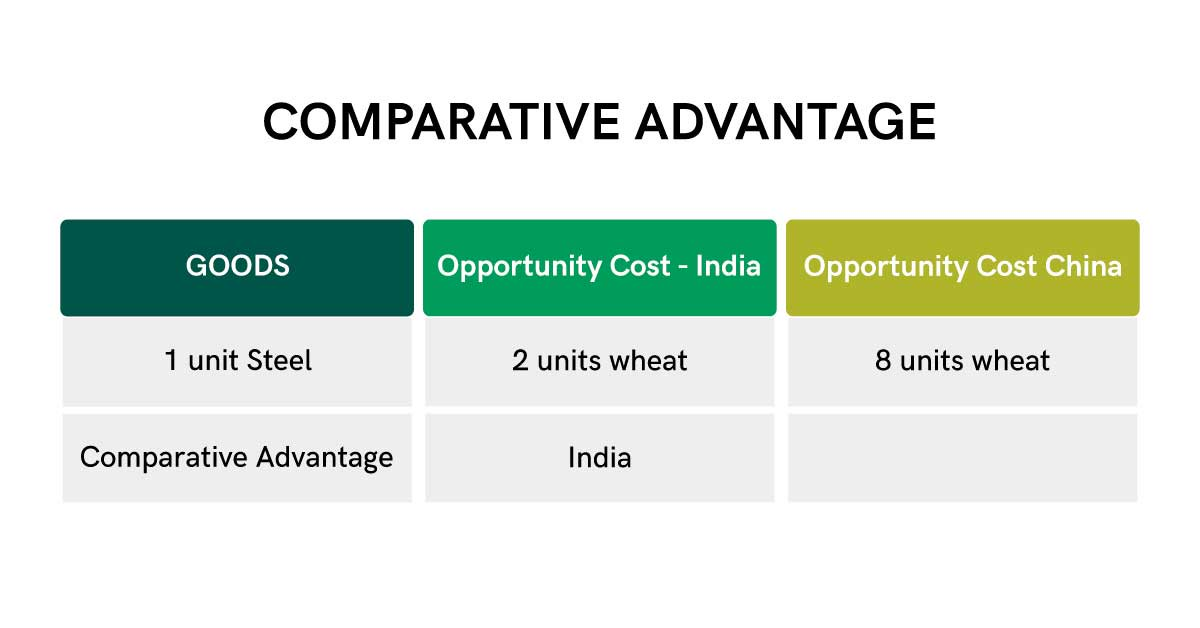

Now stick with me, let’s calculate the opportunity cost for India to produce one unit of steel. Every single time they produce an additional unit steel, it costs them 2 units of wheat.

China on the other hand gives up 8 units wheat for each unit of steel they produce, and since India has a lower opportunity cost, they have what’s called a comparative advantage.

China has a comparative advantage in the production of wheat.

But here’s the best part, if India specialises in steel, they can import wheat from China at a lower opportunity cost than if they produce wheat themselves.

For example if these two countries make a deal to trade 1 ton steel for 4 m tons of wheat, India would be better off.

They would rather get 4 m tons of wheat per ton steel from China than only get 2 m tons per ton steel by producing wheat on their own.

Now, China is also better off. They would rather trade 4 units of wheat for steel than give up 8 wheat for producing 1 ton steel on their own.

Now hopefully your head isn’t spinning.

Being able to do these calculations is good, but it’s more important to understand the main idea.

Individual and countries should specialise in producing things in which they have a comparative advantage and then trade with other countries that specialise in something else.

This trade is mutually beneficial. Now that’s the production possibilities frontier.

Open International Trade: Win -Win For All

In the real world, it’s way more complicated than this simplified model, and we’re only in the beginning.

This graph is super simplified, but the idea that countries should focus on producing the products for which they are better suited is huge.

Way huge!… The graphs aren’t real, but the concepts are.

Another reason you should learn this is because you might hear a politician or someone on the news argue that international trade destroys domestic jobs, and even though it may seem counterintuitive,

economists for centuries have argued that trade is mutually beneficial to whoever’s trading.

And now you know why. Now to be fair, there are all sorts of other intolerable issues associated with international trade, like child labor, dangerous working conditions and pollution, and I will try to address these in the future.

But if there’s one point on which most economists agree, it’s that specialisation and trade makes the world better off.

It’s Mutual!

No country in recent decades has achieved sustained improvements in living standards without open trade with the rest of the world.

Countries like Cuba, Venezuela, Zimbabwe, and Iran that are voluntarily or involuntarily cut off from the world remain less economically developed than they could be.

On the other hand, countries that have opened their doors to trade like Japan and Taiwan, or, more recently, India and China, have seen massive improvements in their standards of living.

Adam Smith was on to something. Self-sufficiency is inefficiency and inefficiency can lead to poverty.

In the next article we will discuss how everything is priced. The answer is surprising. We do. We as consumers are responsible for pricing everything from tomatoes to petroleum. How do we do this? Supply and Demand.

Thank you so much for reading. I’ll see you next week.

The content on this blog is for educational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice. While we strive for accuracy, some information may contain errors or delays in updates.

Mentions of stocks or investment products are solely for informational purposes and do not constitute recommendations. Investors should conduct their own research before making any decisions.

Investing in financial markets are subject to market risks, and past performance does not guarantee future results. It is advisable to consult a qualified financial professional, review official documents, and verify information independently before making investment decisions.

Open Rupeezy account now. It is free and 100% secure.

Start Stock InvestmentAll Category